MIT Technology Review is marking its 125th anniversary with an online series that extracts insights for the future from its historical coverage of technology.

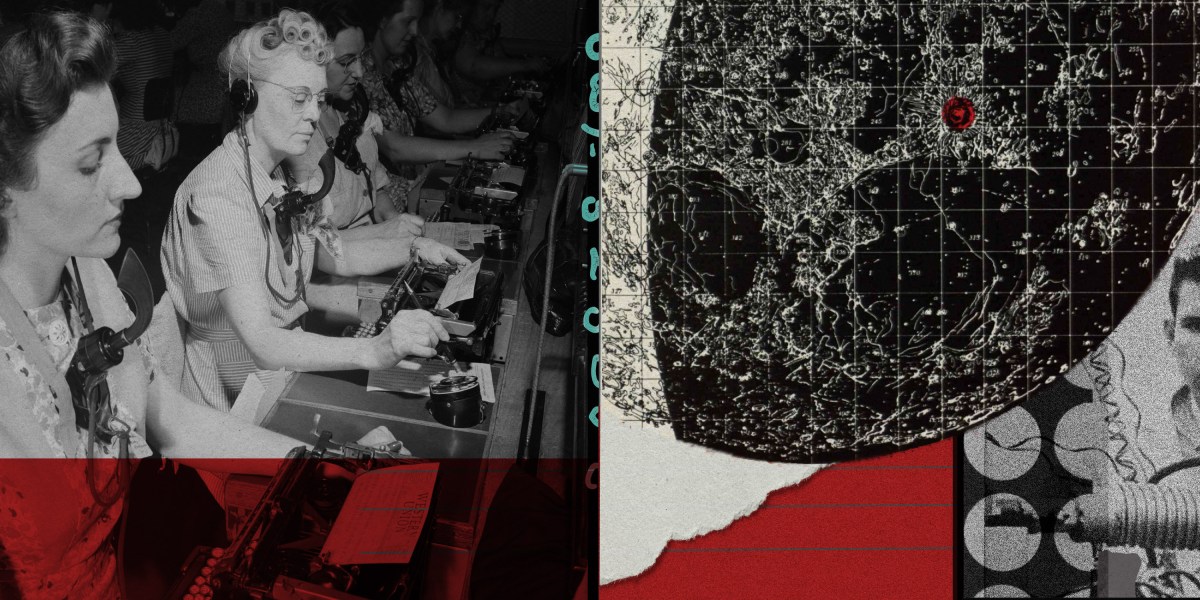

Back in 1938, during the lingering aftermath of the Great Depression when US unemployment rates hovered around 20%, concerns about job security were rampant. The renowned British economist John Maynard Keynes had already sounded the alarm in 1930 about the specter of “technological unemployment,” cautioning that labor-saving innovations were outpacing the creation of new job opportunities. The advent of new machinery was revolutionizing industries and farms, with examples like the adoption of mechanical switching in the telephone network rendering local phone operators obsolete, a profession predominantly held by young American women in the early 20th century.

The pivotal question of that era revolved around the dual nature of technological advancements: were they benevolent genies fulfilling humanity’s needs, or malevolent monsters poised to supplant their creators? MIT’s then-president, Karl T. Compton, a prominent scientist, delved into this discourse in the December 1938 issue of the publication, exploring the concept of “Technological Unemployment.”

Compton’s analysis delineated the impact of technological progress on a macroeconomic scale versus its localized repercussions on individuals. While he argued that, on the whole, “technological unemployment is a myth” as technology catalyzed the creation of new industries and expanded markets, he also acknowledged the acute social challenges faced by displaced workers in specific sectors or communities.

The debate on the interplay between technological evolution and employment dynamics persists, echoing through subsequent decades, including the early 1960s when fears of automation and productivity growth outstripping labor demand loomed large. Notably, an essay by economist Robert Solow in 1962 debunked concerns about mass unemployment due to automation, emphasizing that productivity growth had not reached revolutionary levels. However, Solow recognized the plight of workers whose skills became obsolete in the face of rapid technological shifts.

Fast forward to the present era dominated by discussions on artificial intelligence (AI) and automation, reminiscent of past anxieties over job displacement. The narrative has evolved to encompass the transformative potential of generative AI, smart robots, and autonomous vehicles, sparking debates on the feasibility of a future devoid of human labor. Despite the disruptive influence of digital technologies on various sectors and occupations, the discourse underscores the nuanced interplay between innovation, job creation, and economic progress.

As luminaries like Elon Musk envision a future where AI supplants the need for human labor, pragmatic considerations underscore the imperative of leveraging technology to augment human capabilities rather than replace them entirely. The enduring relevance of Compton’s advocacy for responsible management during technological transitions resonates today, emphasizing the need for companies to prioritize public service over short-term gains and proactively address the societal impacts of automation and AI advancements. In navigating the evolving landscape of work in the AI era, the choice between leveraging technology for job displacement or skill enhancement remains pivotal in shaping a sustainable future of work.