A recent research study published in Ecological Informatics by a group of researchers from the University of Alaska Fairbanks leveraged artificial intelligence to shed light on a habitat exchange involving short-billed gulls.

Traditionally, gulls inhabit coastal regions and areas near water bodies like rivers where they prey on insects, small mammals, fish, or birds.

The research team discovered that during the period from May to August, short-billed gulls frequented locations that were previously dominated by scavenging ravens. These areas encompassed supermarket and fast-food restaurant parking lots, as well as man-made structures like industrial gravel pads and waste disposal sites.

This study stands out as the first of its kind to amass a three-year dataset through citizen science-based, opportunistic research techniques, encompassing a substantial sample of gulls and other sub-Arctic avian species in urban Alaska. It offers a current snapshot of the habitat transition to an urban setting.

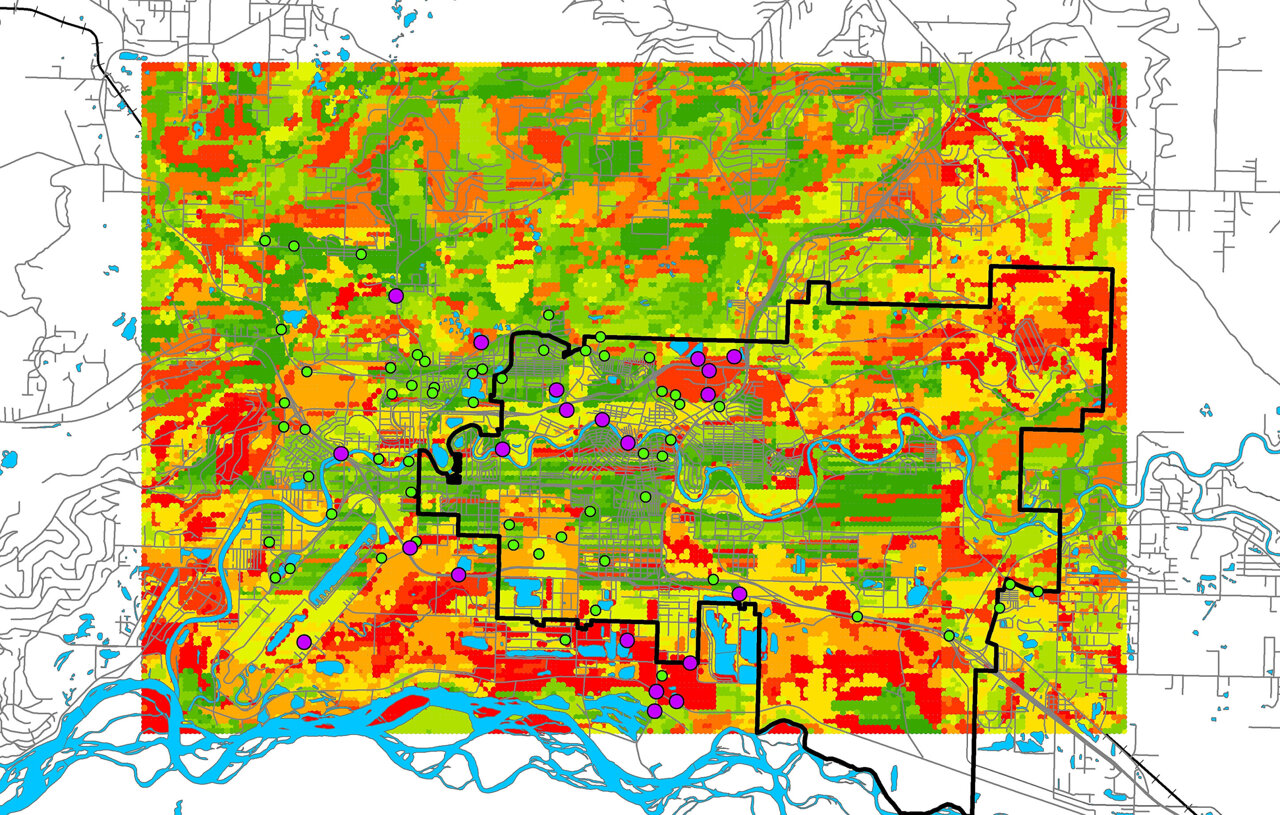

Falk Huettmann, a professor at UAF and the primary author of the paper, along with his team, employed artificial intelligence modeling that utilized environmental factors specific to various locations as predictors to infer details about gull occurrences. A previous study had examined the distribution of the great gray owl using a similar approach.

In this investigation, researchers integrated U.S. census data and urban municipal data such as proximity to roads, eateries, water bodies, and waste management facilities.

Moriz Steiner, a graduate student in Huettmann’s lab, emphasized the significance of incorporating socioeconomic datasets like the U.S. census, stating that it revolutionizes the research landscape by enabling a more realistic simulation of natural conditions through the inclusion of these variables in the models.

The results suggest that the gulls’ shift from their natural habitats to urban surroundings is primarily driven by the abundance of human-generated food sources and industrial transformations.

Huettmann highlighted that the gulls exploit the food resources discarded by humans, with easily accessible but unhealthy options such as salt, fat, sugar, grease, and contaminants found in garbage dumps and fast-food outlets posing risks to the birds’ health and longevity.

Short-billed gulls, previously known as mew gulls until 2021, exhibit omnivorous behavior and exceptional adaptability. While these birds can procure more sustenance from garbage sites and gravel pits, the nutritional quality of such food is often detrimental and can lead to fatalities. The practice of avian “dumpster diving,” particularly at fast-food establishments, can be fatal due to the high levels of unhealthy components.

Moreover, gulls serve as reliable indicators of ecosystem health and disease prevalence. The team observed a rise in disease carriers at locations where gulls congregate, with populations reaching up to 200 birds per site during the summer. Gulls are known to transmit infectious diseases like avian influenza and salmonella, which can be transmitted to humans. Historical records show that the initial documented outbreak of gull-related salmonella occurred in 1959 in North America’s Ketchikan region.

Huettmann underscored the pivotal role of gulls as disease vectors and emphasized the correlation between these avian species and human development, showcasing how disease reservoirs align with areas of human activity.

In Huettmann’s view, these studies underscore the evolving nature of what is traditionally classified as “wildlife.”

He emphasized that such insights offer a comprehensive view of how human activities are reshaping the natural environment and underscored the potential of machine learning to advocate for enhanced wildlife conservation efforts.

For more details, refer to the original research article by Falk Huettmann et al., titled “Model-based prediction of a vacant summer niche in a subarctic urbanscape: A multi-year open access data analysis of a ‘niche swap’ by short-billed Gulls,” published in Ecological Informatics (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2023.102364