When Lyor Cohen first encountered Google’s groundbreaking artificial intelligence concept, he was genuinely amazed. As the global head of music for Google and YouTube, Cohen revealed to Billboard in November that Demis Hassabis, the CEO of Google DeepMind, and his team introduced a research project on genAI and music that truly impressed him. Reflecting on his exploration of London for two days and contemplating the diverse possibilities, Cohen concluded that genAI in music is not just a futuristic idea—it is already a reality.

While some key figures in the music industry have embraced these innovative endeavors, not everyone shares the same level of excitement. This disparity arises from Google training its AI on a wide range of music, including copyrighted tracks from major labels, and then engaging with rights holders without prior consent, as disclosed by sources familiar with Google’s exploration of conceptual AI and music. This approach raises concerns that artists may not have the ability to “opt out” of such AI training, a critical issue for many rights holders.

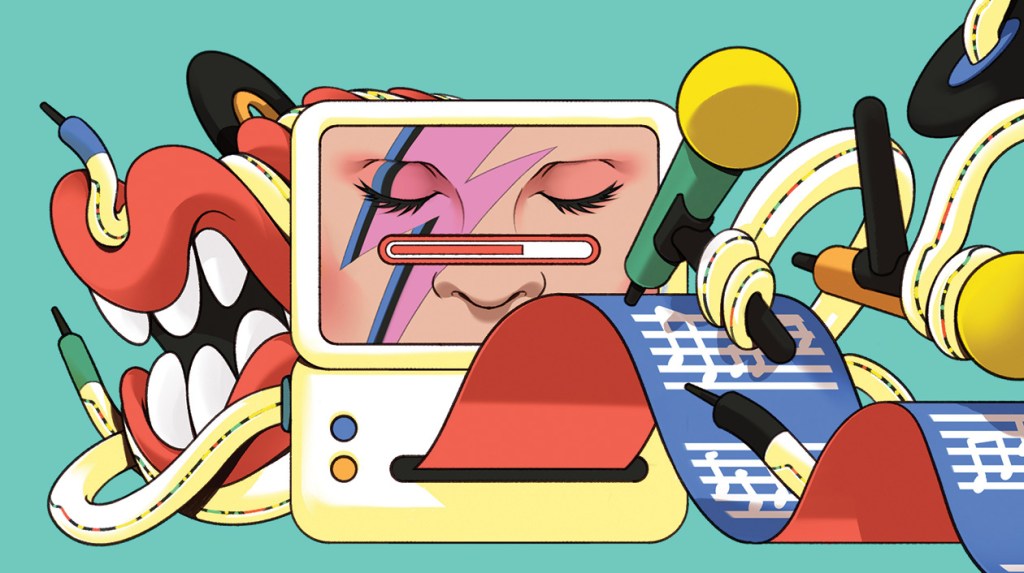

Before unveiling a beta version of their revolutionary genAI “experiment” in November, YouTube took the precaution of negotiating individual agreements with specific functionalities. One such product, Dream Track, the primary AI offering currently accessible to the public, enables a select group of YouTube creators to integrate music into short videos based on text prompts, potentially incorporating voice samples from renowned artists. Notable labels like Demi Lovato and Charli XCX participated in this initiative. Cohen stressed at the time, “Our collaboration with the music industry is a cornerstone of our success.” Nevertheless, discussions that many insiders in the industry see as a model for broader, label-wide licensing agreements have been in progress for years.

In discussions with a corporate entity as significant as YouTube, several sources familiar with the company’s branding talks highlighted the challenges posed by its historical approach of taking what it desired. As other AI companies advance with their music-related offerings, YouTube faces increasing pressure to enhance its technology.

A spokesperson for YouTube, who refrained from divulging further details regarding licensing, affirmed, “We are committed to responsibly advancing AI to offer users lasting opportunities for promotion, controls, and identification of potential genAI tools and content in the future.”

Training is a prerequisite for GenAI models to effectively create content. Google clarified in responses to the U.S. Copyright Office in October that “AI training involves a mathematical process of analyzing existing works to statistically model their operations.” The algorithm gains the ability to predict how new works can be created by deconstructing existing works.

Several lawsuits have been initiated, including Getty Images v. Stability AI and the Authors Guild against OpenAI, to determine the necessity of obtaining consent before utilizing this process on copyrighted works. In October, Universal Music Group (UMG) filed a lawsuit against AI startup Anthropic, alleging that the company engages in “unlawful reproduction and dissemination of extensive copyrighted works while constructing and operating AI models.”

As these legal battles unfold, they are expected to set precedents for AI training, although this process may span several years. Meanwhile, some tech firms appear determined to adhere to Silicon Valley’s ethos of “move fast and break things.”

Tech companies argue that their actions fall under the purview of “fair use,” a U.S. legal doctrine allowing the unrestricted use of copyrighted materials under specific circumstances, while rights holders decry what they perceive as “rights infringements.” Apart from media reporting and criticism, other instances such as parody, various applications, and recording TV programs for later viewing are also covered.

Anthropic, in its submissions to the U.S. Copyright Office, argued that “multiple cases support the idea that copying a copyrighted work as an intermediate step to create a non-infringing output may constitute fair use.” Google’s statements underscored that “innovation in AI fundamentally relies on large language models’ ability to learn computationally from a wide array of publicly available content.”

Ed Newton-Rex, who resigned from his position as Director of Music at Stability AI in November due to the company’s use of copyrighted works for training, emphasized the prevailing approach in the relational AI realm, stating, “When you think of relational AI, you typically associate it with companies adopting a very forward-thinking approach—such as Google, OpenAI—with cutting-edge models that require extensive datasets.” He added, “The concerns of rights holders in this sphere, where substantial data is imperative, are not often a focal point of discussion.”

The fair use argument was challenged by Dennis Kooker, President of Sony Music Entertainment’s global digital business and U.S. sales, during a Senate forum on AI in November. Kooker asserted, “Training a conceptual AI model on music to generate original musical compositions for commercial competition is not a fair use.” He stressed that such training cannot proceed without the consent, acknowledgment, and compensation of artists and rights holders.

UMG and other music labels, in their lawsuit against Anthropic, echoed a similar sentiment, cautioning that AI companies should not be “exempted from adhering to copyright regulations” simply because they offer “significant societal value.”

UMG pointed out that if Anthropic can avoid payment for the content it heavily relies on, it could potentially gain a competitive edge. However, this does not absolve the company from accountability for its extensive unauthorized use of copyrighted material.

Engaging major players early on, as Google and YouTube did with Dream Track, could potentially alter the music industry’s perspective in this landscape, particularly when training models before their release. This approach signifies progress, at the very least, compared to past practices; notably, Google’s scanning of a vast library of ebooks in 2004 without prior consent led to the development of Google Books. The Authors Guild subsequently filed a lawsuit against Google for copyright infringement, though the case was eventually resolved nearly a decade later in 2013.

While the music industry has proposed legislative measures related to AI, the current situation reflects a clash of interests between the two domains. The divergent viewpoints were succinctly captured by Newton-Rex: “What we in the AI field consider as ‘training data’ is what others have long viewed as creative output.”

Bill Donahue contributed to the comprehensive coverage.